I'd like to think that my best clubbing years are ahead of me. Sounds stupid to say at 24. But a long streak of disappointing club nights has been creeping up. My new current location, Rome, makes clubbing even harder. I had a moment of fear that maybe they were over.

Why would I care so much about that? I have not been to raves, I have not been to free parties, I have just started going to festivals, so my best year of partying should be ahead of me — but for some reason, it is the club that I keep longing for —likely, having just re-read in full Sarah Thornton’s Club Cultures contributes to this obsession.

Has clubbing even ever been that fun? Yes, I think so. I have had some really great clubbing experiences, but sometimes it feels like those do not justify my obsession with having one more good club night. Like chasing my first highs, I have kept on trying to experience that euphoria of those first (post pandemic) nights1. While some had in common that I was in an environment different than my usual, in other ways all of those memorable club nights were banal. What distinguishes a good club night from a bad one I am not sure. Music, of course, plays a big role. But so does sound systems, built environment, social environment, political climate, presence and absence and appropriate use of drugs and alcohol, security and door policies, distance from the club space to my bed, outside temperature which influences whether I have to carry a coat or not, price of tickets, price of a locker, did I forget my earplugs, are my shoes hurting, did my friend just ditch me, and so on and so on.

What distinguishes a good club night from a bad one I am not sure, but some last attempts have been a failure. I am not interested in eulogies for club culture. For that, one should have been in it when it was alive, in full force, and I think my presence to it has always been peripheral2. Also clubs are not monolith, they resist generalizations as they are incredibly dynamic spaces that change continuously, influenced deeply by local contexts and local trends. So, here I’m just putting together some preliminary notes and thoughts on the thresholds of club space, with a faint wish to write a hopelessly romantic declaration of love to it. The club is my crush —perhaps because I’ve always seen it from afar, where it looked much hotter.…

The other woman

Something I have been noticing from a tiny window called my phone (which is partial, personalized, algorithmically biased), is a heightened focus on festivals rather than clubs. Perhaps the pandemic played a role, but likely larger trends of soaring rent prices and subsequent diminishing of club spaces might be the culprit. Disproportionate attention on festivals is detrimental to the local nightscenes, which do not benefit from large (and often highly corporate) events running once a year, especially if compared to a habitual form of clubbing ingrained into a routine of entertainment and of experimentation.

In a recent First Floor article, Shawn Reynaldo writes over the supposed suffering of the festival industry, an industry which he says could benefit from some degree of purging, given its bloated state. Reynaldo rightfully points out that the music sector's obsession with festivals, from the perspective of promoters, artists, and consumers, has potentially sucked away energies from local scenes. I too, albeit a tiny one, am a victim and perpetrator of the practice criticized by Reynaldo, which produces a music discourse seemingly only interested in festivals through press partnerships between them and publications. If there was a way to conduct similar style of music coverage for clubs rather than festivals, I'd do it. But the bigger organized events lure you in with full backstage press passes, which an amateur writer or researcher like me will of course take advantage of.

But festivals aside, I think that the perceived imminent death of club culture, or at least its state of malaise, can be analyzed from the rise of a different symptom, one that is much more quiet, distorted, looped, drawn out.

The ambient room

I don't think clubbing has run out of things to say, but maybe it is struggling to find the right way to do so.

I say this, because messages from "club" music still circulate, coming from disparate corners of the sonic landscape. Often times, I have noticed, they come from the ambient rooms, listening spaces, site specific music installations. More and more places feel the need to build an ambient room, either physically, or in terms of programming.

"Ambient rooms" are not new to the club space. The chillout room is a phenomenon present in 90's clubbing, associated with a plethora of genres, from the classic Brian Eno to the Ibiza "chillout music compilations". In this article, Manu Ekanayake identifies a decline of the chillout room following its first adoption in the 90s. The commercialization of each square meter of space, coupled with connotation of drug use, had made a chilling room less enticing to club owners. But spaces for closer listening seem to be popping up again, in different forms such as the room of a club, a bar, ad hoc events. In the article, "techno DJ with an ambient-leaning" Sybil highlights the role of labels such as 3XL, Motion Ward, West Mineral and Appendix.Files, as well as artists like Special Guest DJ, exael, ben bondy, perila, ulla, nueen, nexciya, mu tate and Pontiac Streator in the promotion of a new wave of ambient, especially within the Berlin nightscene.

When I was preparing for the interview I did with James K, I found this album review in which James, Special Guest DJ, and Naemi were described as coming from the “clubby corner of the ambient music scene” — I’ve been carrying that description around in my head since reading it, it’s been such a useful tool in reading the map of my music consumption, which often features the labels and artists mentioned by Sybil.

Some of my favorite musical experiences from the past few years have occurred in spaces proximal to that corner, in the context of a listening event. I'm thinking of some incredible performances at the The Grey Space for Default, SSIEGE for Portraits at the Teatro Basilica, Huerco S. at LOST, in the middle of a bamboo maze. There is no term I deem appropriately describes these varied formats of performing what is usually moody leftfield electronic music live, also because of the infinite possible shapes it can take. But I would argue that these types of events could be put in one (loose) category because of the mood they evoke, the type of listening they require, as well as the genres they propel forward. This expanded form of listening/clubbing can function as breaks into otherwise heady or heavy club nights, it can be the buildup to more active sets, it can be a moment for serious rumination. These experiences united by the music’s capacity of brooding incredibly deep emotional reactions. One can enter a totally personal meditative state while in a crowd, at once isolated in its own personal sonic journey while in contact with a roomful of others seemingly experiencing something similar. A sense of mass synchronicity difficult to replicate in any other setting. Probably the most special setting for this was in the bamboo labyrinth of LOST, where the grass roots of the plants truly felt like they mirrored the connectedness of the crowd. All that hippie bullshit of music brining you together, I felt it.

The creation of these new moments for sound explorations is something I touch upon in my interview with friend of the pod Torus on occasion of his Dekmantel set with Mechatok. Specifically, we focus on a rejection of some aspects of club culture and subsequent expansion into other spaces and forms of clubbing beyond the "classic" four wall space. For him, the embrace of ambient music with its low barrier to entry leads to creation of a safe haven within heady club spaces. Ambient's recognizability through "melodies that are easy to follow and not too harsh, with elements that are highly recognizable" renders it inclusive and allows for experimentation within those familiar sounds. Torus can "stretch and proces sound as far as possible because it will always retain this core of recognizability." Dekmantel's 10 day marathon was an experimentation with stretching the time and space a festival can take, still decisively retaining its festival architecture. While it’s an interesting expansions of clubbing, it seems important to bring back that knowledge to the classic four walls club space — something Torus is hoping to do with Laak's re-opening, whose programming had to fall onto 'listening events' during the 9 month closure due to permit issues.

Not all ambient rooms are created equal, not all live performances of music for DJing are necessary, not every crowd can be asked to listening closely. At Dekmantel's first sunday event at, Het Hem (we could call it the house music day), a room was dedicated to closer listening, laying down on bean bags and such. Upsammy performed an honestly boring directionless set while Jonathan Castro live handled the visuals of a fairly forgettable AV performance. Other times, I have found myself not ready or down for ambient music at 2 am, like the time I was shushed at Laak during some performance at the ambient night — sorry, I did not know we had to bring our whisper voice to the club.

How did we get to this

To me, it is not so obvious that we have managed to bring left field, experimental, boundary breaking genres to the live performance stage. The notion of what counts as "live music" has expanded in many directions. Especially in the realm of electronic music, programmers, artists, labels, and music writers have had to devise ways to create the space, name, and format that render recorded music into a lived, 'live' experience — one that can only be fully experienced by participating in the event and being present. Something which years ago was deemed silly, like facing the DJ at the club, has now become the norm. Turning club music and DJing into a live performance is a fairly recent trend.

A not so brief but necessary dive on the history of Club Music/Club Culture/Recorded Music to Dance to at the Club

In her 1995 book Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital, Sarah Thornton traces the gradual colonization of public spaces by recorded music. The shift from live music to recorded music as the primary form of out-of-home entertainment was shaped by a dynamic interplay of cultural progress and resistance. For instance, in the 1950s, the British Musicians' Union launched a campaign against recorded music, marking the first time the term "live" entered the musical lexicon. This was necessary because, for the first time, records had become synonymous with music itself. Live performances now had to stand apart, promoting their energy and authenticity as the antithesis of what was seen as the "dead" music of recordings. Thornton writes, "The term also asserted that performance was the ‘real live thing.’ Liveness became the truth of music, the seeds of genuine culture. Records, by contrast, were false prophets of pseudo-culture"3.

The place par excellence for the "death" of live music was the disco, often portrayed as generating artificial, superficial, and manufactured experiences. Discos originated in low-budget spaces like schools, community centers, and youth clubs, eventually moving into more commercial settings such as basements or extensions of established venues and bars. By the 1970s and 1980s, these spaces evolved into large-scale commercial discotheques. The cost efficiency of using records fueled a boom in these establishments.

Thornton explains:

"The authentication of discs for dancing was dependent on the development of new kinds of event and environment, which recast recorded entertainment as something uniquely its own, rather than a poor substitute for a ‘real’ musical event. These new time-frames and spatial orders exploited the strengths and compensated for the weaknesses of the recorded medium. By using new labels, rubrics, interior designs and distracting spectacles, disc dances were rendered distinctive. They were effectively transformed from an occurrence into an occasion, from a migrant practice into a unique place, from a diverting novelty into an entertainment institution."4

Hence it was the development of a new type of event, the possibility of creating a new experience, that validated the idea of recorded music to dance to. Records were legitimated by these spaces, and only subsequently was supported by that new establishment in its full blown explosion. The youth as a market determined the unconventional nature of discotheques: "they were lounges, rooms or simply spots; they were places with presence rather than palace (...) The institution continually renovated and effectively rejuvenated itself in order to appeal to an ever-shifting market of youth." (90)

Hence, it was the development of a new type of event, the possibility of creating a novel experience, that validated the concept of dancing to recorded music. These spaces legitimized the use of records, and only later did the records get support in their dissemination from the full-scale commercial explosion of discos. The youth as a market shaped the unconventional nature of discotheques: "they were lounges, rooms, or simply spots; they were places with presence rather than palaces (...) The institution continually renovated and effectively rejuvenated itself in order to appeal to an ever-shifting market of youth."5

DJs, of course, played a central role in the authentication and inculturation of dance and club music, serving yes as artists, but also as representatives of and respondents to the crowds. In orchestrating events and anchoring music in a specific place and moment, the DJ became a guarantor of subcultural authenticity. Initially seen as unskilled workers, DJs quickly elevated their status to architects of musical spaces, using records as raw materials for creative expression through the practice of mixing. This is where Thornton's argument starts to feel outdated. She notes that while DJs may be musicians, they were rarely performers in the traditional pop sense, often hidden away in mixing booths and recognized more by name than face, explaining how “although in the mid-nineties in a minority of London clubs, the ‘cult of the DJ’ led to the practice of facing the DJ booth whilst dancing, this has not been a widespread activity."6

The thresholds of club space

Some of the new attachment towards live ambient sets within the club space feels like a backwash of "live ideology", an aspiration for the left-of-centre electronic artists to a degree of respectability and authority. This also comes from an attempt to dodge the criticism or distinguish oneself from those "show DJs" which, at least on my IG explore page, are constantly roasted for their performative but useless turning of knobs or even worse, playing pre-recorded sets.

This focus does also feels like a way to bring a performative edge to the mix and the remix, a way to actualize a live rendition of what are usually considered "dead" prerecorded genres. In some cases this descends from the cultural lineage of soundsystem culture in which the performance of the record was part of the entertainment. In some others, the performance becomes part of the artist's spiel - I'm thinking specifically of Lorenzo Senni's "crazy" jumping and dancing behind the decks.

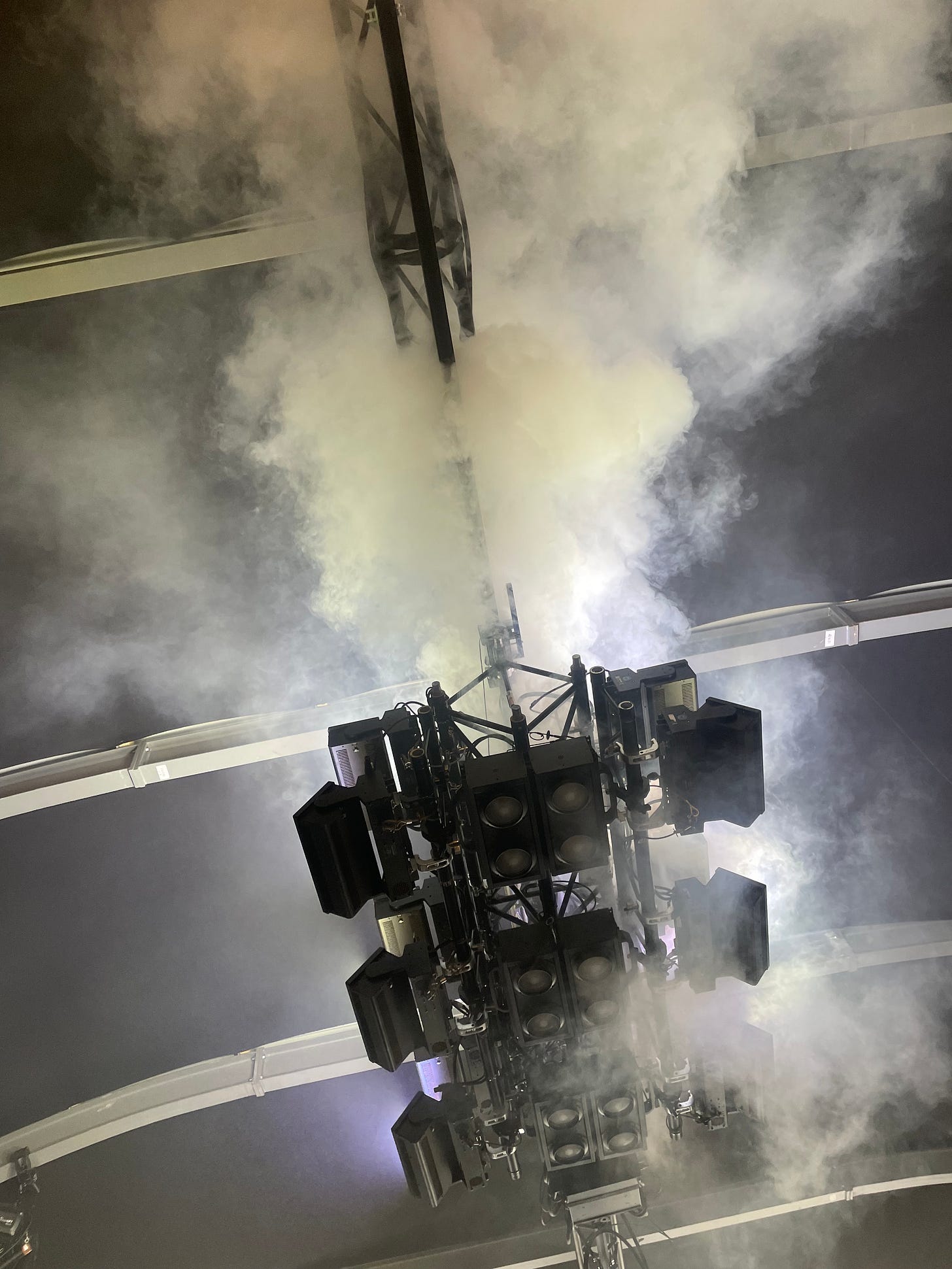

The proliferation of visuals, construction of site specific stages and use of tools for sensory experiences also plays in the lived experience. Dekmantel's impressive architectural and stage design feat, developed in collaboration with studios Dennis Vanderbroeck and Matiere Noire was what stuck most with me. The high production value is felt in the lived bodily experience, the creation of an entirely new, temporary, on-site social space evokes the feeling of a "live" event, despite the "unaliveness" of the tracks being reproduced.

[A parenthesis on my experience of Dekmantel: My honest experience of Dekmantel is that I feel like I didn't experience much at all. Or better said. The festival is a power house, stacked line ups of "legendary names", and an ever expanding geographical reach (I learned from some aussies I met there about the existence of Dekmantel Naarn). Any festival attendee at any festival usually emerges with a different thread of experience, no two journeys are the same. For me, this fragmentation meant that I experienced, at most, a fraction of what was on offer. I tried to plan. For the events at aan ‘t IJ, I sketched out a map of the artists I wanted to see—a futile exercise, it turns out. The tyranny of time and space (and of oddly a not super smoothly organized festival ferry) won. I tried to let myself go to the flow of things. But on Saturday evening I lost track of time and missed the Ben UFO and Joy Orbison set which probably I would have liked. Neither the carefully charted path nor the aimless drift worked as modes of navigation. There must have been a secret third way that I still yet have to figure out —which I hope I will do next time —if there is going to be one.]

So, new kinds of events and spaces are fostering the development of the in-between music genres, the "clubby corner of ambient", which in turn that feeds back into the pool of available events in which to "party" (or nod your head vigorously). Authentication of this experimental side of electronic music is dependent on these new environments, crowds, scenes, "places with presence" - vibes.

Of course, club music still exists and persists, and its most "classic" expressions of it (house, techno, electro) are present at festivals alongside some newer threads and trends (trance, gabber, hardcore, even dancehall, baile and bubbling), Dekmantel being perfect example of this omnivorous lineup. Mine is a genuine and dumb question: do we like where we are extending the threshold of clubbing? This expansion of the club space — will it make my chase of a good club night any easier? I’m not sure.

Whispers from my very personal and very limited experience of music festivals suggests that the new spaces and environments for club/dance music may not the club at all - rather a simulation of it in a hangar, a loop, or its transformation in a new experimental form, a room with bamboo for walls. Some of these simulations absolutely feel like developments in the right direction (any person who has talked to me after LOST quickly got tired of how much I was talking about my incredible experience there). But when pop music tries to tell us club culture is thriving, all I hear is a remix of simulacra and simulations, the distorted and auto-tuned voice of Baudrillard telling us that Brat "simulates" club music as it does not so much imitate, but rather "masks the absence" of it. The clubs are playing "Club Classics" and not the *actual* "classics" in question.

So has club music run out of things to say? Or is it maybe time for a new language?

Few specific memories stand out: oliXL on kingsday night at garage noord, DJ Python at Argo16 the night before in Venice, two days in a row at venue MOT, the first Laak nights (maybe it was still called parallel)

Someone, not me, should write an article called "Club culture is not dead because it was never alive" if you speak Italian this one by friend of the pod/colleague Valerio Mattioli might be close enough, otherwise this Shawn Reynaldo First Floor article might work too - if you can climb past the paywall.

Page 71

Page 85

Page 90

Page 104